The history of Norland in 13 objects: the Norland Quarterlies of World War II

15 December 2022

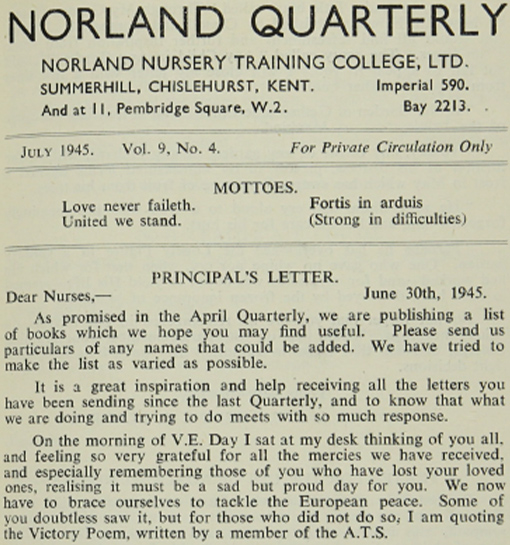

The eighth object in our series of 13 objects that encapsulate Norland’s rich 130-year history, is a selection of Norland Quarterly issues from the Second World War years, 1939 to 1945. These hold letters, notices and articles from staff, students and other members of the Norland community discussing both the operations of Norland during the war but also the experience of living through conflict. They offer a unique commentary on life in war-torn Britain and beyond and highlight how Norland training prepares its graduates for almost anything, then and now.

Norland began to take measures to protect students and children within its care before the Second World War was officially announced in September 1939. Operation Pied Piper (the evacuation system) saw the displacement of 3.75 million people, mainly children, to protect them from German bombing after 1939. However, London County Council approved the process of evacuating young and disabled children as early as May 1938, due to the Munich Crisis (which saw Czechoslovakia sacrifice its borders and defences to Germany). The threat of bombs made the choice a clear one; the Norland Institute must evacuate its nurseries from London.

Principal Ruth Whitehead wrote in her letter in the Christmas 1938 edition of the Quarterly: “The work of the Norland Institute was clear, there were so many children whose parents had to stay in London but who did not come within the public evacuation schemes, who wanted their children to be in a place of safety but would only feel happy if they knew their children were being well cared for as they would by the Norland Institute.”

At first, only 20 nurses and babies were moved to the home of Elizabeth Palmer in Newbury, Berkshire for the small price of one shilling per week. As demand began to rise, Norland quickly outgrew its first lodging. Soon enough, 44 children and 75 nurses descended on their new home of Hothfield Place, near Ashford in Kent. This was a 350-acre estate of rolling fields, a far cry from the evacuees’ city life in London. Their solace was short lived, however, as war was announced, and Kent proved too close to the London bombs to safely house Norland’s charges. “By May 23rd the coast of France was in enemy hands, Kent was a military area, and we made the decision to move to Devon – a decision which ultimately was a happy one, as later we should have been forced to leave”, wrote Mrs Whitehead in the Christmas 1940 edition. Norland, again, packed up and moved to Belvoir House in Bideford, North Devon in 1940.

Yet, this proved only to be Norland’s penultimate wartime relocation. As the war continued, and London was at the forefront of the horrors of the Blitz (1940-41), Mrs Whitehead was succeeded as Principal by Catherine Blakeney in 1941. Mrs Blakeney made the decision in 1943 to gradually move Norland completely out of London for the first time to Chislehurst in Kent, where it would remain until 1967. Although it would take several years to complete the move, with all Norland staff finally saying goodbye to London in 1949.

Even though continuous relocation can be unsettling for small children, they thrived under the round-the-clock care of the Norland nurses. Having experienced their formative years living amongst the horrors of the Blitz, little evacuees often showed signs of trauma. Doris Card’s entry to the Summer 1941 Quarterly offers insight into how the nurses were able to support their charges. “Lately we have had children from bombed homes”, wrote Doris. “One little couple aged 2 and 4 have been bombed twice. They were so limp and cold when they first came and would do nothing but sit by the fire. Now, after three weeks of comparative peace, they play quite happily with other children.”

Displacement was rife throughout the war years, and Norland was no exception. In the Christmas Quarterly of 1941, editor and Norland Registrar, Ruth Hewer chose to forego the address section of the newsletter as it was impossible to maintain. “We know how very disappointed so many of you were last year, not knowing where any of your friends were… but it is not possible to prepare them under the conditions, we did not lightly break this long tradition but so many of you were moving place to place, packing and unpacking and getting acclimatised to the changed and rather primitive conditions of country evacuation to which you are all so accustomed now.”

Displacement and poverty meant access to phones was rare, so the only way Norlanders could regularly communicate was through letters and addresses provided by the Quarterly. Mrs Hewer’s decision meant that many were cut off from their friends as “addresses changed so constantly that the lists would have been out of date before they were even printed.”

Continuous displacement often meant many were left without homes to return to. In the summer Quarterly of 1943, Mildred Hastings (referred to as a member of the ‘founding trio’ of Norland alongside founder Emily Ward and first Principal Isobel Sharman) finished her letter with a plea. “To those who know me I am at present homeless and have no idea where I shall settle after the war is over.” At her time of writing, Mrs Hastings was on a visit to Norland at Chislehurst, joining the hundreds throughout the war who sought respite within the Norland community.

Since Norland’s founding, Norlanders have travelled the world through their careers. Many found themselves in occupied territory or accidently in the front lines. Nurse Pauline Smith submitted a letter to the Norland Quarterly over the Christmas period 1942 documenting her station in Paris. She wrote of the atrocities: “I have seen people rummage in dustbins outside for leaves of cabbage, potato peelings or rotten oranges and they were glad to find them…. All surplus supplies are taken to Germany and Italy and it is maddening to see your stocks go like this.” Many civilians were forced into poverty and “have been fainting in the streets and in the trams from lack of nourishment and they have much less resistance to disease just now.”

Norlanders across occupied Europe were often left vulnerable as British citizens abroad and given their refusal to back down to Nazi ideology. Pauline explained, “for a year or more we lived under a very black cloud, afraid to speak even to our best friends, sometimes we were even afraid to think.” Living under Nazi rule was suffocating for all but being a foreign-born employee could raise suspicions that they were part of a spy-network. “We were all watched, and there were days when I know I was followed… German propaganda is prolific, French papers are censored and no British or American films are allowed.”

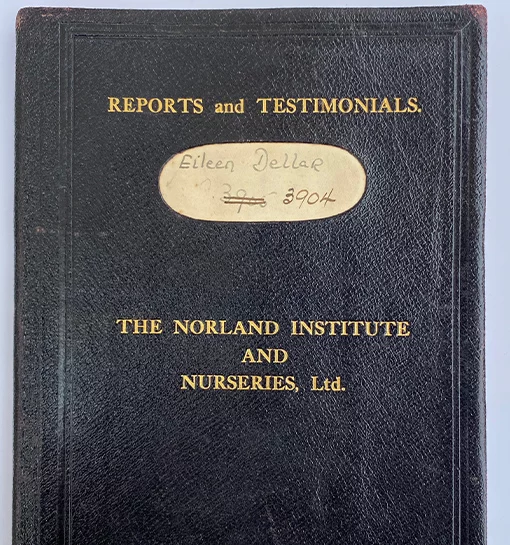

One Norlander, Ivy Crewe, found herself imprisoned in a Nazi Prison Camp stationed in Brussels. The Countess E E de Armie was also a prisoner there, and when she was eventually liberated, she described her post-war reflections in The Evening News, proclaiming that even in such terrifying conditions, Nurse Crewe remained true to the Norland mottoes of ‘Love Never Faileth’ and ‘Strength through Adversity’. “Even after she had been to hospital for scarlet fever, she returned to take up her nursing. If anyone deserves a medal, that woman did.” Ivy Crewe was known within the prison camp to take care of ailing prisoners, entertain the children and support their mothers, even though she was an ailing prisoner herself. A true testament to the ethos Emily Ward established at Norland in 1892.

Unsurprisingly, during the war years, it became increasingly rare for Norlanders to retain their posts as nursery nurses. The National Service Act of 1941 required all women between the ages of 20 and 40 to register for wartime work. The Star reported in August 1941 that “owing to a shortage of children’s nurses many mothers are looking after their own children as a spot of war service.” Due to the intensity of the war effort, many women were sent to fill the roles of men going to war and cuts were made wherever possible. All nursery nurses were commissioned to start operations within the war-time day nurseries, only with rare exceptions. This measure lasted until the end of the war. “You will find it exceedingly difficult to get a Norlander for your child”, stated The Evening News in July 1944, “a Norland trained girl is not allowed now.”

Bombing intensified during the final years of the war and Norland’s haven at Oakleigh in Devon was subject to attack in the early hours of 21 March 1944. The on-duty nurses were quick to action and evacuated the children and staff to Millfield. Thankfully, there were no casualties, only a night of broken sleep for the little charges. June of 1944 saw the arrival of flying bombs, which caused Norland to close for three months. Children who could not return to their parents were taken into the homes of Norland students.

It becomes evident when examining Norland during the war years, that the training prepared the students not only to care for children. Elizabeth Robertson wrote a letter to the Christmas 1945 Quarterly describing her and fellow Norlander Edna Gotobed experiences working in the Belsen Concentration Camp only four days after its liberation by the British Army. “We consider it to be a great privilege to be here”, she wrote, “Edna is a Health Visitor in Camp 4 —the show place of Belsen—with over 2,000 Poles. I am in mothers and babies camp 111 which has a more varied population of 6,000… most of the mothers were caught in the Warsaw Revolution of just a year ago. Their babies have been born since in a concentration camp… they know nothing of their husbands or other children, they hope they are still in Poland.”

During both World Wars, Norlanders positioned themselves on the front lines. From joining the Voluntary Aid Detachment and providing vital military assistance during the Great War, to volunteering in liberated concentration camps. Each Norlander, then as now, embodied Norland’s founding mottoes. Most recently, these core traits of love and resilience were mirrored during the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw Norlanders and students supporting frontline health workers, volunteering to help their local communities, and leaving their own homes and families to support shielding families in need.

Today, Norland’s ethos continues as it did in 1892. Its thorough training and education prepares its graduates for anything they might encounter throughout their careers, and a love of caring for, and nurturing others, remains at the heart of its approach.